by Howard Hanson

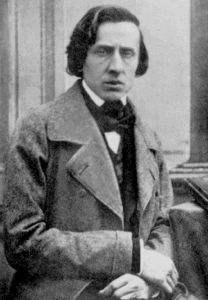

What is left to say of Chopin, this genius whose gifts blossomed so naturally and gracefully, with an inward complexity that baf les theorists and an outward simplicity that communicates to the least learned listener? Nothing could add to the memory of his greatness, or increase the affection in which his music is held.

We may pro it, however, by considering his creative philosophy, and learn lessons for our own age. To me, as a composer, three of these lessons stand out.

First, humility. Chopin learned early in his short life that it is not the form one uses but the expression one pours into it. He wrote for that least exotic of instruments, the piano. He might have written symphonies or operas or string quartets, but chose to remain with the one instrument through which he could express himself most naturally and effectively. He taught us that it is as important to write a song as it is to write a symphony.

Second, simplicity. Chopin was an artist who believed in music as a means of communication from the composer to all people. He wrote, “A long time ago I decided that my universe will be the soul and heart of man.” No matter how intricate the inner construction of his music is, it does not demand a highly trained listener. The construction and craftsmanship only assist our understanding.

Third, healthy nationalism. Chopin was irst of all a composer of Poland. He sang of his own land, of his own people and he communicated the spirit of Poland to the rest of the world through the language he spoke so eloquently. It is frequently said that music is an international language – by which nation speaks to nation – and perhaps it is. But it could also be

Chopin spoke to the world, but he spoke in his own tongue, through his own experience. Into that language went the love of his friends, of his neighbors, of his country. For this reason he will always be remembered as the most precious jewel in Poland’s crown–a great nationalist who spoke to all nations, in sincerity, simplicity, and beauty––an artist who mirrors the soul of Poland itself.

Frideric Chopin… Poland’s musical soul

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin was born in Poland on or about March 1, 1810, th son of Mikolaj Chopin and Tekla Justyna Krzyzanowska. His father, thought born in Eastern France from which he emigrated to Poland in 1787, considered himself Polish. Fryderyk was the second of four children, and the only boy. He Was born at Zelazowa Wola, just West od Warsaw, where his father was teaching French to children of the nobility. Shortly afterward the family moved to Warsaw, where for the next 27 years Mikolaj was a respected professor of French.

During 1826-1829, Chopin sometimes accompanied his classmates to their homes, where he experienced peasant music during harvest festivals. In Silesia he notated many tunes that later influenced both the style and content of his compositions. During 1828 he traveled to Berlin and saw various operas and oratorios. He was greatly impressed by the work of George Handel.

In 1829 Chopin ended his formal education at age 19 and went with acquaintances to Vienna, where he gave two highly successful concerts, playing his Variations on a theme from Mozart’s Don Juan (op.2), and Rondo a la Krakowiak (op.14). The following year the Variations were published in Vienna, his first composition published abroad.

Returning to Warsaw in 1829, Chopin experienced a period of a year during which he composed and performed his Concertos No. 1 and 2 in E minor (op.11) and in F minor (op.21) for piano and orchestra and many other shorter compositions such as mazurkas and etudes. He gave a number of public performances, including two in the National Theatre, to high acclaim for his remarkable virtuosity. Chopin was invited his admirer Count Antoni Radziwill, Governor of Poznan, to go to Berlin and be introduced to the musical milieu there. However Chopin elected to return to Vienna, the scene of his recent success. He gave a farewell concert in Warsaw in October, 1830, Playing the Concerto in E minor, and on November 2nd departed Poland, not knowing then that he would never return. His friends gave him a chalice of Polish earth to take with him.

In Vienna he and his friends became aware of the November 1830 Uprising against Tzar, which was crushed in a few month, sending Chopin into a black period of depression. his diary says “… I can only groan, suffer, and pour out my despair at the piano.”

In july 1831, at age 21, Chopin left Vienna for Paris, traveling through Salzburg, Munich and Stuttgart, where he performed his Concerto in E minor with the Philharmonische Verein.

Chopin’s residence in France, where he lived in the 18 years before his death, was his period of greatest productivity. His great love of Poland, to which he was politically prevented from returning, shined through his many compositions like a beacon. Chopin composed continuously, and gave lessons to many students. He met Rossini, Liszt and Berlioz. Robert Schumann called Chopin a genius. One of his greatest admirers was the German poet Heinrich Meine. In 1834, when he met Felix Mendelssohn was so greatly impressed by his virtuosity that he wrote that Chopin “played the piano as Paganini played violin”

Until 1835, the number of his performances that he was in great demand. He often performed in Paris at the Salle Pleyer, owned by Camille Player, whose Player pianos where particularly studied to Chopin’s style of playing. He said that they allowed him more control of the sound than other instruments he used a Playal “pinion” when teaching students, who played on his Playel grand.

Chopin’s affliction with tuberculosis became evident when he was about 25 years old. This disease, which was widespread in Europe at the time, he caused the death of his father and of his sister Emilia. Although in a debilitated condition, he continued to compose, and to travel. His compositions swelled his lifetime output to prodigious proportions. In addition to his two concertos, Chopin published 16 Songs, 12 Polonaises, 57 Mazurkas, 27 Etudes, 25 Preludes, 19 Nocturnes, 13 Waltzes, and Rondos.

Chopin never married. At nineteen in Warsaw, he became enamored with the singer, Konstancja Gladkowska, who appeared on the same program where his Concerto in F minor premiered. He left Warsaw at age 20 without pursuing that relationship. in 1835, at age 25, he asked for the hand of Maria Wodzinska of Dresden, and was accepted on the condition that he would take care of his health. In the year following, his health deteriorated and the family rejected him as unsuitable for Maria. He bundled her letters and labeled them “My Sorrow”. In 1836, he met the novelist Amantine Dupin, who wrote under the pseudonym “George Sand”. She had been married and was six years older than he. He later formed a relationship with her that lasted until his death. George Sand had homes in Nohant South of Paris, and on the Island of Majorca. She and Chopin visited these homes often in the years from 1838 until his death in Paris of tuberculosis in 1849. Though gravely ill, he continued to compose, to travel, and perform. His last Public concert was in London on November 16, 1848, benefit for veterans of Warsaw Uprising of 1830. Shortly before he died he took an apartment in Paris at Place Vendome 12, and his elder sister Ludwika came from Warsaw to take care of him. He received the last rites on October 15, 1849, and died on October 17th, 1849, at age 39.

Chopin’s funeral was held in the Church of the Madeleine, with the Mozart Requiem and music for the mass. His body was buried in the Perl Lachaise Cemetery in the Perl Lachaise Cementary in the Eastern part of Paris, but as he requested, his heart was removed and taken in urn to Warsaw by his Sister Ludiwka. Visitors to Warsaw can see in the Church of the Holy Cross the memorial pillar where his heart reposes, there in his beloved Poland.

For Poles, Chopin’s music was like

“Cannons hidden under the flowers”

About the Author

Distinguished composer HOWARD HANSON, then Director of the Eastman School of Music, was a Kosciuszko Foundation Trustee and Chairman of the Chopin Centennial National Committee, assembled in 1949 by the Kosciuszko Foundation to coordinate 100th Anniversary of Chopin’s death.